Paul Bear Bryant's Last Magic was Spent on Tuscaloosa, Alabama and Crimson Tide Football

- Mark Schipper

- Feb 23, 2021

- 12 min read

Updated: Jul 25, 2022

By Mark Schipper

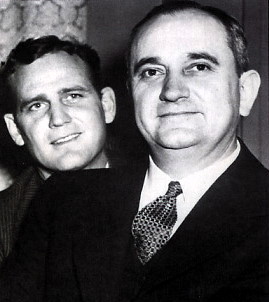

“Forget it, it’s all changed, they took it away from me,” Paul Bear Bryant said, referring to the committee convened to hire his successor at the University of Alabama.

That approach, which sounds misguided for all the obvious reasons, turned out to be folly. And it must have been some heady blend of ambition, envy, and hubris that drove a quintet of academics to ignore the proffered wisdom of a college football Demigod, deferring instead to their own greenhorn judgement in picking not one but two coaches who hadn’t appeared anywhere on Bryant's list. The Crimson Tide, after forsaking the Bear's final instructions, drifted rudderless for seven-years before they could atone for their grievous error.

“I think they thought Bryant was old or whatever and they just didn’t go by his wishes,” said Jack Rutledge, one of Bear’s personal assistants who'd worked with the old ball coach unto the day of his passing.

Atop his list Bryant had proposed Gene Stallings, his former player at Texas A&M and assistant coach at Alabama, to replace him. He'd included a backup name as well but conferred with Stallings and expected the university to acquiesce to what was, frankly, his unimpeachable judgment on the matter. When the university ignored him, and then skipped over his second candidate as well, the Bear—dangerously unhealthy and exhausted—threw in the towel. Twenty-eight days after he had coached Alabama to a final victory—a Liberty Bowl triumph over Illinois in the dusky, frosty December cold at Memphis, Tennessee—he was dead.

As the world moved on without the Bear in it, Stallings settled into the National Football League, coaching several more seasons with Tom Landry and the Dallas Cowboys before accepting a head job with the St. Louis Cardinals. But Stallings kept an eye on the Crimson Tide each autumn, quietly confident in the knowledge the Bear had picked him to tend the sacred fire in Tuscaloosa, even if it hadn’t come to fruition for reasons beyond both their controls.

“There ain’t no question what Bryant wanted,” Stallings later said, referring to the snub of nineteen-eighty-two.

WHO WAS THE BEAR?

The program chief the bureaucrats ignored in their coaching search reigns today as one of the mystical monarchs of college football, the chairman of the board at a Coaches’ Valhalla. Using the leverage of school bylaws, and the back roads of procedure, to ensure Bear Bryant did not get to pick your next football coach was like handcuffing King Midas on the off chance the things he touched might break rather than turn to gold. Yet that was exactly what the administrators at Alabama did.

Bryant, over thirty-eight seasons, had traveled the coaches' long course of honors to the pinnacle of the sport. After playing a strong end for Alabama between 1933 and 1935, doing yeoman's work on the undefeated national champions of 1934, Bryant began coaching in 1936, inaugurating a seven-year apprenticeship under coaches as legendary as Frank Thomas and Red Sanders at Alabama and Vanderbilt Universities, respectively.

He had accepted the head coaching job at Arkansas in 1941, his first opportunity after three-quarters of a decade hard work, and was on the road to Fayetteville when he got word the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. Bryant literally turned the car around and drove home, ditching his first big break to enlist in the Navy, where he served as an officer during World War II. But rather than send Bryant off to fight in the Pacific Theater, they had him coach service football instead.

Delayed by three years, Bryant returned to civilian life and entered the first phase of his head-coaching journey, taking over the decrepit program at the University of Maryland. Almost overnight he became one of the game’s most compelling young program chiefs, a coach whose intense drive in practice shocked both his players and the curious crowds that began showing up to watch the way Bryant drilled a football team into order.

After a single season at College Park, during which he took the Terrapins from 1-7-1 to 6-2-1 overnight, Bryant suddenly quit and fled from Curly Byrd, the autocratic university president who had been meddling with his coaching staff and players during the offseason. Bryant had another job immediately, driving himself and his young wife five-hundred miles southeast to Lexington, where he took over another floundering program at the University of Kentucky.

Again, it took the Bear just one offseason to build a winner in the Blue Grass state. After getting the Wildcats from 2-8 the year prior to his arrival to 7-3 during his opening campaign, Bryant churned out eight of the best teams the school's ever had, going 60-23-5, including an outright SEC championship in 1950. The Wildcats have not won an SEC crown in the seventy-two subsequent falls. That 1950 season had climaxed in a Sugar Bowl upset over Bud Wilkinson’s mighty Oklahoma Sooners, the greatest bowl victory in program history and an 11-1 record to go with it.

Bryant moved on from his now formidable Kentucky program following a 7-2-1 season in 1953, both to escape the dwarfing immensity of basketball coach Adolph Rupp—who despite rumors of hostility was in fact a personal friend—but even more so an administration that had broken promises made to the football program, an unforgivable breach of integrity to an old-fashioned bondsman like Bryant.

By the time Bryant walked away from Kentucky he was a nationally recognized talent with nearly a decade of high-end production at mediocre football schools as proof of his unique effectiveness. These seasons, during what could be described as a career middle period, were marked by the coach's implacable, almost menacing drive to prove his skillset was worth the steepest valuation the market would stand. The Bear uprooted his wife from the easy comforts of old-money Lexington and planted the family in the empty, barren heat of College Station, Texas, where he would coach Texas A&M the next four autumns.

During his first season at Aggie-land Bryant carried out the most infamous training camp in college football history. In a barren, drought-dry, cocklebur-spangled sandbox at Junction City, Texas, Bryant drove the roster he'd inherited beyond its breaking point. From a group of around one-hundred athletes bussed out to the ramshackle, satanically-hot quonset huts at Junction City, thirty-eight survivors returned to College Station, with the rest either having quit or snuck home over the course of the ten day camp. One of those survivors had been Gene Stallings.

"Quitting never entered my mind," Stallings later said. "I never gave it a thought. I tried to get a heat stroke, but I never once thought about packing up and going home."

The Junction Boys returned home and promptly went 1-9 in 1954, the only losing campaign in Bryant's thirty-eight years coaching. But that was the end of the bad times for his teams at A&M. That same group improved to 7-2-1 the next fall, finishing second place in the Southwest Conference. The next year, with Bryant's recruits taking the field alongside the core of Junction Boys, the Aggies went 9-0-1, outright SWC champions for 1956. The Aggies had gone from the doldrums of college football to the doorstep of a national championship in three years.

After a final 8-3 campaign the next season, and his valuation as a program leader approaching the national Gold Standard—“Momma called” Bryant home for good. The Bear returned to Tuscaloosa as the picked savior for his alma mater, the man Alabama fans hoped could pull them out of a nosedive and return them back to championship glory.

Bryant would pass the next twenty-five autumns in Tuscaloosa, where he had played and then worked under the great Frank Thomas, a coaching legend in his own right who'd quarterbacked Knute Rockne's early Notre Dame teams before leading the Crimson Tide to two Rose Bowls and two national championships. After taking over a program with an 8-29-3 record in the four years since its 1953 SEC championship, Bryant needed four seasons of his own to bring the Crimson Tide back to the pinnacle of the sport.

The Bear won the first of six national titles in 1961 with an 11-0 squad, and then sustained a two-decade run of championship excellence that had no precedent in major college football. He would retire the all-time winningest coach in the history of the sport, passing Amos Alonzo Stagg and Pop Warner in his final season to finish with 323 victories, including 14 SEC titles and 20 bowl wins, between 1945 and 1982.

WHO WAS STALLINGS?

Over the course of those thirty-eight campaigns the Bear produced forty-six branches on his coaching tree, as former players and assistants were hired away as head men at both college and professional outfits. While a famous teaching philosophy has it that the high-water mark of success is for a student to surpass the teacher, the Bear himself did not subscribe to that belief. Over the decades Bryant ran up a 43-6 record against former players and assistants—professionals in their own right who often admitted it had been difficult to suppress their awe of the man—while annihilating any ambiguity about the nature of the relationship.

But Stallings carried a rare pelt from one of those victories, taken off the Bear at the 1968 Cotton Bowl in Dallas. Bear had loved Stallings as a player at A&M and kept him as an assistant for seven seasons at Alabama. Largely on the strength of Bryant’s recommendation Stallings had become the head coach at Texas A&M.

Just three years later young Stallings led the Aggies to a grinding, 20-14 victory over the Crimson Tide in the mud-spattered, surprise-cold of that New Year’s Day at the State Fairgrounds. It was more than just a win over the Bear, it was a big-bowl upset on national television against the program of the decade and an offense led by first-team All-American quarterback Kenny 'the Snake' Stabler, who was playing his final game for the Crimson Tide.

As the clock at the Cotton Bowl ticked to zero the Bear had pulled low his houndstooth and got to looking mighty shifty as he snuck through the postgame scrum to shoot in on Stallings like a wrestler, lifting him off the ground and making a 'you son of a bitch, you beat me,’ turn before putting him down. Stallings smiled and laughed, half bewildered by what was happening, as the press cameras snapped away and captured the entire moment. That the Bear, who hated losing with an existential dread possibly equaled by the combined angst of Vince Lombardi and Napoleon, was that happy for Stallings’ victory, said more than any words could about his regard for the man.

Bryant's esteem for Stallings came in part from a kind of shared kinship. Both the Bear and Stallings were tough old war horses who lived by personal codes that meant more to them than conventional morality. Back in 1963, with Stallings in his sixth year as an assistant in Tuscaloosa and Joe Namath Alabama’s star quarterback, Stallings had made a memorable stand in the name of personal integrity. During that crises, which severely tested Bryant at a moment when he was king of all he surveyed across the Southland, Stallings had helped the Bear remember himself.

Joe Willy—a Southern nickname bestowed on Namath, a well-loved Northerner from Western Pennsylvania—was the greatest quarterback in college football. Alabama’s offense, which had begun passing the football more than any other team of Bryant's career, took flight off the whip and snap of Namath's right arm. But Namath, after the Crimson Tide’s upset loss to Auburn, their first Iron Bowl defeat since 1958, had been caught drinking—a forbidden pastime during the season—and a report of the incident had reached the Bear.

In an intense man-to-man conversation at the offices in the football-residence building—already called Bryant Hall—Namath admitted to beers with a group of friends over at Captain Cooke’s tavern. Looking down at his chastened quarterback, Bryant's face full of a heavy, furrowed grimness that felt to Namath like the judgement of god, Bryant had grumbled: “Joe, I can either suspend you, or I can let you play in these last two games, and then I’ll have to resign. Cause if I let you play I’ll be violating all my principles of coaching.”

“No, coach, I don’t want that to happen,” Namath replied, with the devastation of what he had done crashing in. “I’ll take my punishment.”

But even Bear, whose laws were carved into stone tablets, was in this case full of dread and indecision. This was not just a superb quarterback or the team's professed leader—Namath was a good kid—the player Bryant later called “the greatest athlete” he’d ever coached. So Bryant gathered his assistants for a meeting and, to the stupefaction of everyone present, suggested the matter was open for further discussion.

What ought to be done about Namath?

Every assistant, from offensive coordinator and future hall-of-fame head coach Howard Schnellenberger, to Bryant's favorite defensive line coach Dude Hennessey, wanted to keep Namath active for the season’s final two games, including the Sugar Bowl against Ole Miss. Everyone except young Stallings, the twenty-seven-year-old survivor of the Junction Boys camp. Stallings wanted to know what alien life force had invaded the body of Bear Bryant.

Stallings said Namath deserved to be suspended for breaking the team’s rules, period.

“If it had been me, you’d have kicked me off,” he said to Bryant.

With the votes in, the meeting ended, but it wasn’t a democracy. The program's potentate retired to make a final decision. The next day Bear announced the suspension—telling everyone except Stallings they had not been thinking about what was best for Joe Namath or the Alabama football program, only what might win the next football game. Bryant ordered them to begin preparing for the final two games without the sport’s best quarterback. That was the cost of the infraction and the program would pay it.

That Stallings was the man Bear wanted back in Tuscaloosa to lead the program. And the man the coaching committee, chaired by university president Joab Thomas, could not envision a future with. So the Tide wandered their seven years in the wilderness, first with a coach so defiant of the Bear’s imprint he became obsessed with obliterating it. And, after he'd been chased off, a second coach so overawed and haunted by the ghost he'd replaced he couldn't think straight, eventually fleeing the job of his own volition.

All the while the program’s passionate, disillusioned fan base—a collective that wanted Bryant back so badly it would have sold its collective soul at the crossroads to bring him back—grew restless.

THE RETURN

Then, like it was meant to be, the second coach walked away after the 1989 season, unable to settle into a situation where the invisible energies felt charged up against him. Stallings, who was in a bad spot under notoriously fickle ownership in St. Louis, had been forced out five games into the NFL's season and was looking for work. The moment had arrived for Alabama to stop trying to outmaneuver fate and hire the man the Bear had tapped on the shoulder. So they did, and, as the famous book says: It was good.

At the introductory press conference Bear’s son, Paul Junior, known as a quiet and private man, delivered the blessing and anointment. In a room full of media and former Bryant players, Paul Junior had hugged Stallings and then turned to the microphones: “This is exactly what papa wanted,” he said.

Stallings was the right man for the post in large measure because he knew how to handle the Bear's ghost. Like most football men who'd had extended contact with Bryant, Stallings never fully got over his awe, and didn’t want to—the study at Bear’s school had given him too much. But what Stallings had that some others did not was a deep peace with himself as a coach and a man. He would use where it was useful what the Bear had shown him, but he wouldn’t try to be the Bear or some ersatz copy of him

"First of all, you have to know what Alabama football is about, and it's about Bear Bryant,” Stallings said at the press conference. "He is the standard here, and everybody gauges you by him. I have no problem with that. I am not Bear Bryant, can't be Bear Bryant and can't coach his style. But, in my opinion, you have to hold on to what he left here. I wish I could consult with him.”

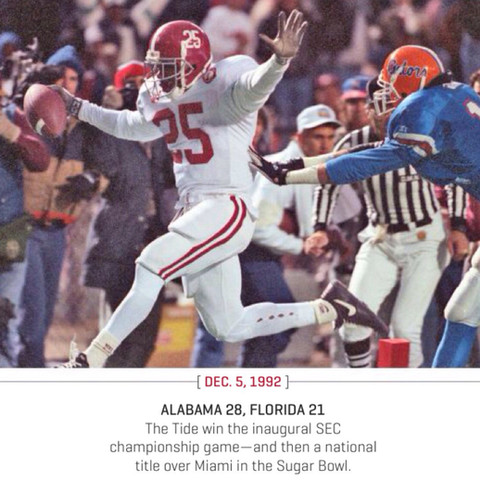

Three seasons later, the low and gruff-voiced Stallings—he did sound a little like the Bear—had restored order to the realm. His teams had both halted, and reversed, a four game losing streak to their deadly rival Auburn in the Iron Bowl. Then, in 1992, the Tide won the Southeastern Conference title outright with an undefeated record, a run which included an epic, cold-blooded triumph in the first SEC Championship game over a superb Florida Gators team coached by Steve Spurrier, the lethal revolutionary on the brink of a hostile takeover of the Bear’s old realm.

Crowned the SEC Champions, Stalling’s team went down to New Orleans, the spiritual capital of the South, and manhandled the undefeated, defending national champion Miami Hurricanes in the Sugar Bowl, where the Bear had led so many teams to glory in decades gone by.

The rout had begun with a ferocious, bullying defense, the way Bear loved it, that had dismantled Miami’s mighty offense in the Superdome, essentially bludgeoning the most intimidating program in college football into submission before the game was through. Alabama had allowed only 13 points while returning an interception—one of three that night against the Hurricane’s Heisman-winning quarterback—thirty-one-yards for a defensive touchdown.

The offense, a run-dominated, field position playing, conservative passing affair—the Bear’s preferred mixture—put up 27 points to go with the pick-six for a clean 34 on the night. The victory snapped Miami’s twenty-nine game winning streak and ended what had appeared destined for back-to-back championships for the best program of the nineteen-eighties.

Alabama’s win, as it turned out, closed out the tab on the Hurricane’s decade of dominance and destruction, it would never be the same for them again.

The victory, the entire season, its style and strategic approach, had been a Bryant Special made up the old way from beginning to end. As the huge Alabama crowd at the Super Dome roared into the night, and the Tide's players poured onto the field with Stallings hoisted onto their shoulders, college football in the South was, for the Alabamians, put back to rights. The mystic chords of memory sounded throughout Tuscaloosa as the team struck camp to come home with another title.

Stallings, in recognition of his 13-0 national championship team, was awarded the Bear Bryant Coach of the Year Award by the Football Writer’s Association of America. It was the last of the Bear’s potent magic and he spent it on Tuscaloosa and his old friend, Stallings.

Whaddya know about all that?

Comments